We are delighted to present the very first Annual Industry Insights Report from The Association for Business Psychology (ABP). This report represents a significant milestone in our mission to be “the home and voice of Business Psychology in the UK.” Key Points: Value of Business…

Article based on webinar delivered September 2024

Author: Charlotte Housden (Sheridan), Business Psychologist and Chartered Coaching Psychologist

As children we spend a lot of time playing, having fun and being curious about the world. Over time, this can fade away until, as adults, we’re persuaded that this is too childish and inappropriate for work. I’d like to encourage you to think differently.

A few years ago I was working towards becoming Chartered as Coaching Psychologist. I had to write a long form academic essay and chose to focus on playfulness and humour in coaching. I asked myself whether this: “could they be used to build trust and deepen a relationship with clients?”

My resulting 6,478-word essay was neither playful, nor humorous, but that wasn’t its job. However, I did discover evidence that they can be very helpful in our work. First, let’s start with what we mean by humour and playfulness. This is where the first challenge arrives. The literature and research is complicated – for example, there are 184 definitions of playfulness and over 20 theories of humour!

Some researchers describe them as behaviour, others personality traits, some research focuses on their impact on wellbeing, others look at how it impacts our work. In fact, many researchers conflate the two ideas. I therefore decided to create my own definition to include them both:

“Playfulness and humour (P&H) is emergent and spontaneous and most likely to arise in relationships which have rapport, and are trusting, honest and open. How P&H is expressed will vary widely, depending on the individuals and context, but when used intentionally, authentically, and collaboratively, it can provide space for clients to discover new perspectives, creatively explore ideas, lighten challenging moments and experiment with different ways of being. Over time it can deepen relationships, especially when co-created.”

Here is more on playfulness:

- There are different types: cheerful-engaged, whimsical, impulsive, intellectual-charming, imaginative, light-hearted and kind- loving – Proyer (2012)

- It may enable stress reduction and coping strategies – Magnuson & Barnett (2013)

- “Enjoyment of playing with thoughts and ideas, embracing complexity and taking different perspectives” – Wheeler (2020)

- “Predisposition to frame (or reframe) a situation” – Barnett (2007)

Playfulness can therefore be a coping mechanism and can manifest in many different ways, as well as being a way of standing back from challenges to see them in a fresh light. I told you it was complex! And now for humour:

- It can create enhanced relationships, more collaborative negotiations and better customer relations – Cooper & Sosik (2012)

- “An emotional leveller” which “brings people together and helps them connect” – Ludlow (2022)

- Can lead to improved group cohesion – Romero & Pescolido (2008)

- A healthy way of distancing from problems and gaining perspective – May (2009)

As you can see, this area of research isn’t going to win awards for clarity. However, we can benefit from thinking about how we engage with our colleagues or clients and how we use humour and playfulness in our work.

In September 2024 I ran a workshop for the ABP on this as a way of sharing my research and offering an opportunity to reflect on how we use it in our practice. My aim was to ask participants this: “when can we use it and when is it best to steer clear?” We might consider the benefits it can bring, e.g.:

- Creating more engaging and memorable learning

- Building better relationships

- Fostering creativity and innovation

- Providing perspective on challenges (plus increasing the likelihood of their resolution)

- Raising levels of happiness and self-esteem

- Supporting people to create effective coping strategies

It’s important to flag that playfulness isn’t just being childish, it can be bringing a lightness of touch, a way of seeing the world differently. Humour can be a way of embedding ideas and helping readers or participants to engage with content at a deeper level. Here are three examples of its use in practice:

- “I can bring lightness to my coaching through play. I tend to be a fairly serious sort and pretty much all of my clients want to have more fun.” – Whitmire (2018)

- A coach’s client walked outside for a change of perspective. He had been focusing on cognitive problem solving, so she tried something playful: “‘What would the tree think?’ An invitation to have more distance from the issue, to be an observer…” Playfulness “encourages curiosity and a lightness even with really difficult subjects.” – Sheather (2022)

- I used humour in my book, Swim, Jump, Fly: A Guide to Changing Your Life, about successfully navigating change (based on interviews with 108 people in 27 countries). Many reviews highlighted the benefit to learning: “It’s simultaneously both light and powerful, a real achievement. The cartoons are a lovely addition, breaking up the text and bringing the stories alive.” – Sheridan (2022)

Whilst researching for the essay, it became clear that there are downsides too.

- Shadow sides of humour – showing off, avoiding issues, caricaturing others and denying responsibility

- Aggressive and self-defeating humour (e.g. sarcasm) creates dissatisfaction in relationships, anxious attachment, neuroticism and low self-esteem

- Can be used to belittle, laugh at, or mimic a client to create feelings of superiority

- We can wield power over clients creating an out of balanced relationship

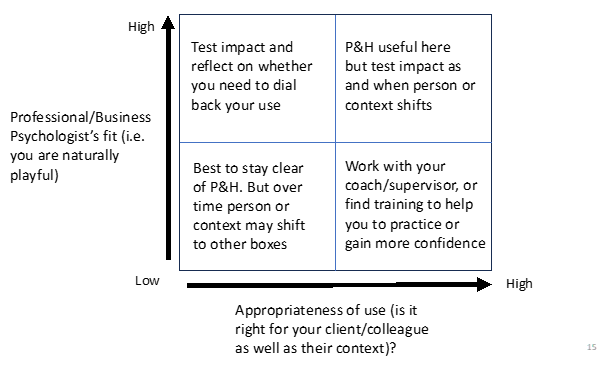

One way to address my earlier question of “when can we use it and when is it best to steer clear”, is to use the model below. I created this to help me reflect on this myself. During the workshop I also invited the participants to try this out. First, take a look at the model and familiarise yourself with the quadrants.

Now pick a box that fits you best now. Reflect on whether you might flex into other areas by asking yourself:

- When could I dial up P&H to create stronger relationships?

- When might I use P&H to encourage better problem solving?

- When should I really dial P&H down?

- What else might I try to shift in some way?

Here are two ways to test it out. In therapy Dryden used to tell jokes to gauge his client’s “humour quotient”. In coaching or training I use self-deprecating humour to observe the client’s reaction. I might also try a small playful move to judge their receptivity.

During the workshop we also had a go at using a playful exercise – Liminal Muse Conversation Cards which is a facilitation and reflection tool I developed using my photography. Participants were able to use it ask themselves some questions whilst also being playful and giving themselves some room to stand back from the topic.

So, have I encouraged you to think more about humour and playfulness in your work? I do hope so. Why not let me know how you get on.

References:

Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of playfulness in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.018

Cooper, C.D. & Sosik, J.J. (2012). The laughter advantage: Cultivating high-quality connections and workplace outcomes through humor. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Oxford University Press.

Liminal Muse Conversation Cards: https://liminalmuse.co.uk

Ludlow, I. C. (2022). Humour In Psychoanalysis and Coaching Supervision: From Life to Interventions. Routledge.

May, R. (2009). Man′s Search for Himself. W. W. Norton & Co.

Magnuson, C. D & Barnett, L. A. (2013). The Playful Advantage: How Playfulness Enhances Coping with Stress. Leisure Sciences, 35, 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.761905

Proyer, R. T. (2012). Development and initial assessment of a short measure for adult playfulness: The SMAP. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(8), 989-994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.018

Romero, E. & Pescosolido, A. (2008). Humor and group effectiveness. Human Relations, 61, 395-418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708088999

Sheather (2022), in Lancer, N., Wheeler, S., Love, D. & Sheather, A. How can coaching help me be more creative? The Coaching Psychology Pod, 1(8). https://www.bps.org.uk/member- networks/division-coaching-psychology

Sheridan, C. (2022). Swim Jump Fly: A Guide to Changing Your Life. Charlotte Housden Consulting Limited.

Wheeler, S. (2020). An exploration of playfulness in coaching. International Coaching Psychology Review, 15(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsicpr.2020.15.1.44

Whitmire, A. (2018). What learning about my coachees’ narratives taught me about my own – Part 1. https://learninginaction.com/coachees-narratives-own-part-1/

Charlotte Housden is a Business Psychologist and Chartered Coaching Psychologist. She runs a consulting practice working with clients to build leadership development, coaching and talent management programmes, alongside, coaching senior executives who are managing change in their organisations or careers. You can contact her on LinkedIn or at ch@charlottehousden.com. Her book on navigating change is available on Amazon or on the swimjump.com website.