What does a great day at work look like for you? Is it flying through your to-do list, to earn a quiet afternoon? Maybe it’s a hectic schedule, jumping from meeting to meeting, feeling productively busy? Or perhaps, it involves reaching a key milestone, feeling…

‘‘More Connected, but Disconnected?’’

Author: Shaun Biggs

There has been an increase in remote working availability for employees over the past two decades, influenced by increased technological advancements and the focus on work-life balance. Remote work is a workplace option that enables individuals to permanently work from an alternate location outside of the traditional workplace housing the organisation’s offices (Wiesenfeld et al., 2001). In the 12-month period to December 2019, there were 32.6 million people in employment in the UK. Of these, around 1.7 million people reported working mainly from home, with around 4.0 million working from home at some point in the week (Office for National Statistics, 2020). However, this growing trend raises the following question:

Has remote working made it increasingly challenging to keep employees engaged with their organisation and subsequently fostered the likelihood of professional isolation?

Although there is a perception that remote working will give employees benefits in terms of flexibility and autonomy, this is countered by questions regarding employee well-being (Charalampus et al., 2019). Literature on the association between flexible working practices and employee well-being has provided mixed opinions. Ter Hoeven and Van Zoonen (2015) claimed that increased flexibility around work locations would lead to greater work-life balance, job autonomy, and effective inter-employee communication, resulting in enhanced staff well-being. On the other hand, remote workers should not be allowed to become “invisible workers”; they may be very skilled at their job, but they do still require support from their organisation to be effective (Grant et al., 2013).

A wide range of factors, such as quality of working relationships with leaders, communication, and trust can all affect the remote workforce. These exterior factors are often discussed, but any insight into an individual employee’s ability to adapt to the remote working environment would give a distinct advantage to the organisation. Employee’s unique personalities, needs, and motives interact with organisational factors to influence engagement levels and isolation. Fulfilling these needs becomes more difficult outside a traditional working office. A remote worker may become detached and feel these needs are not being met remotely.

For some, remote working greatly improves their work life balance, enabling them to match, and potentially increase, their previous levels of productivity. This makes them more likely to remain with the organisation. For others, remote working can bring negative consequences, including feelings of isolation, lack of engagement and a drop in productivity. Conversely, this makes them more likely to leave the organisation. This will ultimately impact the performance of the organisation.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has thrust the discussion of whether remote working will become the ‘new normal’ into the mainstream narrative. Organisations have been energetically evaluating the benefits of remote working, which include saving money on office rent, increasing employee productivity and providing a better work-life balance for their employees. Whilst these benefits are important, there needs to be an acknowledgement of the role that individual differences have on employees. The impact of these individual differences will have intensified when the workforce has been put into ‘sudden remote working’ by the COVID-19 pandemic. If organisations are going to take advantage of the opportunities provided by remote working, it will be of benefit to understand the personality characteristics of their employees and how they can affect employee engagement or feelings of isolation and aid in better employee performance.

The current research investigates the influence of personality traits in the context of remote working, with a focus on employee engagement and feelings of professional isolation.

This Research

The researcher employed a quantitative online survey design which incorporated the use of a personality assessment and established surveys measuring worker engagement and professional isolation (loneliness). One hundred and seventy-seven participated in the research, of which 75.1% reported some level of remote working in their average working week. The research provides a unique perspective on remote working because the data was collected during a four-week period of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. This is apparent by 66.1% stating they have been remote working for three months or less.

Personality

Personality traits play an important role in what kind of emotions individuals can experience (Yunus et al., 2018), suggesting that not all individuals would benefit to the same degree from remote working. It feels like common sense that someone who is extraverted or low on conscientiousness may face different and potentially more significant challenges when remotely working alone. Failing to take individual differences and environmental issues into account can risk poor performance and disengagement. Meeting the specific needs of different staff members will increase their feelings of connection with the organisation. The next step of the research was to identify a suitable assessment to measure personality.

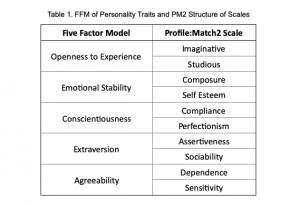

Profile:Match2 (PM2; Trickey & Hyde, 2014) is a psychometric assessment developed by Psychological Consultancy Ltd. PM2 is based on the ‘Five Factor Model’ (FFM) of personality, which is the most prominent and influential model of personality in contemporary psychology (Barańczuk, 2018). The FFM of personality consists of the five broad domains of ‘Neuroticism’ (emotional instability vs. stability), ‘Extraversion’ (vs. introversion), ‘Openness’ (curiosity or unconventionality), ‘Agreeableness’ (vs. antagonism), and ‘Conscientiousness’ (constraint vs. disinhibition) (Widiger & Crego, 2019). PM2 translates the five FFM factors into ten scales (two per factor) (see Table 1). This enables the assessment to provide a more detailed analysis of personality and more nuanced interpretation in its reports.

Employee Engagement

An engaged workforce is important for organisational effectiveness. When remote working, it can be difficult to gauge whether an employee is engaged because of the distance between employee and employer. If an employee is engaged there is a strong direct association with affective commitment and a strong inverse association with turnover intention (Saks, 2006). Employee engagement has also been linked to increased productivity, financial returns, and sales (Lin et al., 2016). This research hypothesised that employees who are more extraverted will be more engaged in the remote working environment. Extraverts’ need for social interaction will lead to them seeking out engagement with colleagues, despite not being in physical proximity.

The 17-item ‘Utrecht Work Engagement Scale’ (UWES; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003) was used to measure the participants engagement at work. This questionnaire consists of three subscales measuring ‘Vigour’ (energy), ‘Dedication’ (commitment), and ‘Absorption’ (concentration). Participants rated their level of agreement with seventeen statements using a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (‘Never’) to 6 (‘Always’) (e.g. ‘At my work, I feel bursting with energy’).

Professional Isolation

Remote working is often a solitary task completed by the employee within the home or whilst commuting between numerous office locations. Research has shown that working mainly from the office resulted in an increased experience of inclusion in their departments, compared to employees working mainly from a home, a satellite, or a client based office (Morganson et al., 2010). Organisations need to monitor feelings of professional isolation within their remote workforce, as ignoring this issue may be detrimental to their job performance (Golden et al., 2008). It was hypothesised that people scoring lower on the ‘Emotional Stability’ scale were more likely to experience loneliness as a remote worker. Low scorers on ‘Emotional Stability’ are likely to be self-critical and generally more worried, leading them to feel anxious and isolated when working remotely.

Professional Isolation was measured using Russell et al.’s (1978) 20 item UCLA-Loneliness Scale in a work context where participants indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (‘I Often Feel This Way’) to 4 (‘I Never Feel This Way’) (e.g. ‘I am unhappy doing so many things alone.’)

Findings

The purpose of this research was to investigate whether individual personality traits moderate workers’ engagement and professional isolation. The results from the analysis suggests that there are significant relationships between individual personality traits and employee’s feelings of engagement and isolation.

Both PM2 scales within the Extraversion factor – ‘Assertiveness’ (0.229) and ‘Sociability’ (0.190) – were found to have significant positive correlations with employee engagement. Employees who score high on these scales are achievement oriented and energetic (assertiveness) and are outgoing and attracted towards opportunities for social interaction (sociability).These results support previous research findings that certain personality traits are determinants of employee engagement (Akhtar et al., 2015) and suggests this is still the case in remote workers.

Both PM2 scales within the Emotional Stability factor – ‘Composure’ (-0.308) and ‘Self-Esteem’ (-0.337) – were found to have a significant negative correlation with loneliness and isolation. The findings show that employees who scored lower on the Self-esteem and Composure scales of PM2 reported feeling more worried and anxious, and experienced higher levels of loneliness in a remote working environment.

An interesting additional finding also emerged at the analysis stage. The professional isolation analysis, combining PM2 ‘Imaginative’ and ‘Studious’ scale to re-create FFM trait of Openness to Experience (0.224), reported a significant positive correlation with loneliness and isolation. Employees who scored higher on the Imaginative scale (0.233) of PM2 suffer higher levels of loneliness while remote working. These individuals will be curious and innovative about the way things work, which may lead to them feeling isolated and restricted if they are remote working.

The findings from this research demonstrated that personality traits have a significant relationship with an employee’s level of engagement and feelings of isolation. Subsequent regression analyses indicate that that these personality traits account for 6.8% and 20.9% of the variance in engagement and isolation outcomes respectively. These are significant results, especially when a regression analysis of both indicators – engagement and isolation – found that combined personality predicts 29.0% of the variance between individuals. These findings also suggest that there are other factors affecting variances in engagement and isolation in the remote workforce. For example, the age of an employee predicted 4.1% of the variance of an employee’s engagement.

Practical Implications

Employee engagement has a positive relationship with a variety of organisational measures of performance (Saks, 2006b). Evidence points to engaged employees being four times as likely to recommend their company’s products or services (Harmeling et al., 2017; Temkin Group, 2016). Golden et al. (2008b) found that professional isolation among teleworkers was negatively associated with job performance.

While personality is not the sole factor in predicting engagement and professional isolation, these results suggest that incorporating personality assessments as a diagnostic tool in a company’s remote working strategy could provide valuable knowledge about their employees to assist in intervention decision-making.

Specific actions include the following:

- Whilst personality assessments like PM2 have long been used to improve recruitment processes (e.g. Hogan & Holland, 2003), this research also demonstrates additional predictive power. The information they providecan help target early interventions that limit deterioration of employee well-being.

- To prevent those who feel intense emotions from suffering from isolation (i.e. lower on the PM2 composure scale), the organisation can adopt the SHARE approachto managing your remote employee. SHARE is a psychologically informed approach designed to support remote working by recognising the risks for physical and psychological health and addressing these, understanding diversity, and using flexible approaches as every situation will be different, providing support and ensuring people feel appreciate (BPS, 2020).

- Focus on results rather than activity. People managers should set clear expectations about the way employees should deliver and receive communications throughout the working day. This approach will help those higher on the PM2 assertiveness scale to keep engaged, and help alleviate the pressure and anxiety associated with isolation, on those employees lower on the PM2 self-esteem scale (CIPD, 2020).

- Employees high on the PM2 Imaginative scale enjoy discussing and debating issues and may become jaded if tasks are narrow and repetitive. Organisations can help them feel less isolated by building communication-enhancing mechanismsinto the team environment (SIOP, 2012).

- To maintain engagement from employees scoring higher on sociability, organisations should be encouraged to create social support networksbetween remote workers, colleagues, and supervisors (Charalampus et al., 2019b). Maintaining high-quality interactions with managers and co-workers is important for workers’ performance and well-being within remote work situations (APS, 2020).

In the remote workforce, psychological assessment could provide a distinct advantage in managing and understanding the individual differences in employees and how to get the best out of their performance whilst protecting their mental well-being.

About the Authors

Shaun Biggs is a cohort on the Psychological Consultancy Ltd Student Sponsorship Programme and is currently studying an MSc in Occupational Psychology at The University of the West of England. Shaun graduated with a first class honours BSc in Applied Accounting at Oxford Brookes University and is from an analytical background. Shaun has an interest in how psychological assessment and data analytics can assist with improving employee well-being and encourage social mobility. Recently, Shaun completed a project for TMP Worldwide titled ‘You want Real Change for Social Mobility? Let the data guide us!’ which has been shortlisted for the 2020 ABP Award for Excellence in Diversity and Inclusion.

Dr Simon Toms is a Chartered Psychologist and Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society. In 2019, he was elected to Full Membership of the Division of Occupational Psychology. He is also a Chartered Scientist with the Science Council, Principal Practitioner with the Association for Business Psychology, published author, and PhD graduate. He currently works for Psychological Consultancy Ltd in the role of Principal Research Psychologist.

Disclaimer

All contents used in this blog article are owned by Psychology Consultancy Ltd and were originally published on the below web page: https://www.psychological-consultancy.com/project/does-personality-moderate-employee-engagement-and-professional-isolation-in-the-remote-workforce/

Content may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, distributed, downloaded or transferred in any means without the consent of Psychology Consultancy Ltd.

References

Akhtar, R., Boustani, L., Tsivrikos, D., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2015). The engageable personality: Personality and trait EI as predictors of work engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 44-49. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.040

APS. (2020). APS Backgrounder Series: Psychological Science and COVID-19: Working Remotely. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/backgrounders/backgrounder-covid-19-remote-work.html

Barańczuk, U. (2019). The five factor model of personality and emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 217-227. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.025

BPS. (2020). Working from home. Retrieved from https://www.bps.org.uk/coronavirus-resources/public/working-from-home

Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., & Michailidis, E. (2019). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers’ well-being at work: A multidimensional approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 51-73. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2018.1541886

CIPD. (2020). Getting the most from remote working. Retrieved from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/flexible-working/remote-working-top-tips#73357

Golden, T. D., Veiga, J. F., & Dino, R. N. (2008). The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1412-1421. doi:10.1037/a0012722

Grant, C. A., Wallace, L. M., & Spurgeon, P. C. (2013). An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Employee Relations, 35(5), 527-546. doi:10.1108/ER-08-2012-0059

Harmeling, C. M., Moffett, J. W., Arnold, M. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2017). Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 312-335. doi:10.1007/s11747-016-0509-2

Hogan, J., & Holland, B. (2003). Using theory to evaluate personality and job-performance relations: A socioanalytic perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 100-112

Lin, W., Wang, L., Bamberger, P. A., Zhang, Q., Wang, H., Guo, W., . . . Zhang, T. (2016). Leading future orientations for current effectiveness: The role of engagement and supervisor coaching in linking future work self salience to job performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 145-156. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.002

Morganson, V. J., Major, D. A., Oborn, K. L., Verive, J. M., & Heelan, M. P. (2010). Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements: Differences in work-life balance support, job satisfaction, and inclusion. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(6), 578-595. doi:10.1108/02683941011056941

Office for National Statistics. (2020). Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK labour market: 2019. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuklabourmarket/2019

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600-619. doi:10.1108/02683940610690169

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Test manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Unpublished manuscript, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Retrieved from http://www.schaufeli.com

SIOP. (2012). Improving Communication in Virtual Teams. Retrieved from https://www.siop.org/Business-Resources/Remote-Work

ter Hoeven, C. L., & van Zoonen, W. (2015). Flexible work designs and employee well-being: Examining the effects of resources and demands. New Technology, Work and Employment, 30(3), 237-255. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12052

Tempkin Group. (2016). Employee Engagement Benchmark Study, 2016 Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-temkin-group-research-shows-that-successful-firms-have-more-engaged-employees-300220067.html

Trickey, G., & Hyde, G. (2014). Profile:Match2 Technical Manual. Retrieved July 3, 2020, from /wp-content/uploads/PM2-Technical-Manual-LA-150118.pdf

Widiger, T. A., & Crego, C. (2019). The five factor model of personality structure: An update. World Psychiatry, 18(3), 271-272. doi:10.1002/wps.20658

Wiesenfeld, B. M., Raghuram, S., & Garud, R. (2001). Organizational identification among virtual workers: The role of need for affiliation and perceived work-based social support. Journal of Management, 27(2), 213-229. doi:10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00096-9

Yunus, M. R. B. M., Wahab, N. B. A., Ismail, M. S., & Othman, M. S. (2018). The importance role of personality trait. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(7), 1028-1036. doi:10.6007/ijarbss/v8-i7/4530