Authored by Certified Business Psychologist Laura Howard. Certified Business Psychologist, Laura Howard, reflects on the webinar she recently delivered to ABP members. Below she outlines the main findings of her published research uncovering systematic barriers women face when being authentic as leaders. Importantly, she gives…

Author: Leanne Kenyon

Leanne is a PhD student studying creativity and innovation interventions in business at the University of Hertfordshire, having graduated from MSc in Occupational Psychology in 2019. She has spent 6 years working in Knowledge Exchange, supporting collaborations between businesses and universities on innovation projects and is currently a part time Marketing Executive for PraxisAuril.

Dramatizing child prodigies is a long-standing favourite of storytellers, Hollywood and biographers. They focus on some innate, almost magical ability that is un-understandable and intangible to us mere mortals. These are the creative geniuses that were just born better at something and we look on in awe. But these stories rarely tell the full or realistic story. Which is why my recent binge watch of Netflix’s The Queen’s Gambit left me (a psychology PhD student studying creativity in industry) so excited! [#SPOILERS!].

Based on the novel of the same name by Walter Tevis, Elizabeth Harmon (Beth), is the genius, chess playing protagonist, portrayed as someone with obvious difficulties, but never formally diagnosed with a particular mental illness. Of course, being based in the 50’s & 60’s, that in itself could be considered very accurate and it was only her later addiction to alcohol and tranquillisers that stopped her functioning in her normal life.

But still, she became known as a formidable and creative chess master. As quoted in the series, she was too old to be considered a prodigy, but still extremely young, and with no ‘formal’ chess tutoring. In fact, without even a board of her own(!), she managed to absorb everything she needed by seeing the game in her mind (via the ceiling).

My favourite thing about the series is that it showed the importance of domain knowledge. Stories of creatives like to make it sound that these new ideas come from nowhere, but often skip the long, boring sections of just, working hard. Beth had a clear aptitude for patterns and a good memory, but she still had to be taught the rules of the game. And then the ‘style’ of the game (“it’s not a rule, its sportsmanship”), how to play the player opposite, how to play ‘your game, not theirs’. Throughout her life, she had mentors that taught her what she needed relevant to the level she was at. Her orphanage janitor Mr Shaibel, played her in the basement, taught her plays and chess notation, and gave her first chess book. Of course, the rest of the world didn’t see this weekly tutorage or her practicing in her head and so it seems inexplicable.

Beginners’ luck is sometimes confused with creativity, and you can see the similarities. Someone plays a move that is allowable within the rules, but that is totally unexpected by the seasoned pro, sometimes even leading to a win for the newbie. But they would not be able to explain what they had done. In fact, they themselves would probably be unimpressed and confused by their own actions. The creative thinker, however, makes their move for a reason. They know the domain rules so well, that they know how, and when, to break them.

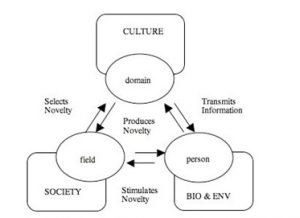

“For creativity to occur, a set of rules and practices must be transmitted from the domain to the individual. The individual must then produce a novel variation in the content of the domain. The variation then must be selected by the field for inclusion in the domain” (Csikszentmihalyi 1999: 315)

The field of course is what recognizes a new move as creative. Something can be new to yourself, and that can feel creative, but a field of other experts that know the domain and the rules as well as the creative person does, needs to be able to recognize that it is a novel contribution, and is relevant to the context, usually for the domain’s overall betterment.

The Consensual Assessment Technique (CAT) (Amabile, 1982) is sometimes called the gold standard of creativity assessment and is used in most domains in the ‘real world’. It works by asking experts in the field to rate the new artefact. “The CAT is based on this idea that the best measure of the creativity of a work of art, a theory, or any other artefact is the combined assessment of experts in that field.” (Kaufman, Plucker & Baer, 2008). A nod to this in The Queen’s Gambit is where world champion Luchenko applauds Beth for being a marvel, claiming, “I may have just played the best chess player of my life”. This assertion coming from a world champion has great meaning! We believe he knows what he is talking about; if he claims it, it’s probably true. But if any of Beth’s fellow orphans had said the same, or the high school chess club, or even the highest rated player in her first tournaments – it would not have been enough to widely accept her as a creative thinker in the domain.

There is another important point relating to the field, and more relevant to creative thinking in a business context, and that is the importance of teams. Although a formidable player in her own right, the higher through the ranks of masters Beth became, the more she learned from mentors and colleagues. This culminated in her overall success of becoming the world champion, by accepting the support of a team of experts back home in America that, by phone, ran through all potential plays to the game, played devil’s advocate, and helped her think through new challenges.

However, there is an ongoing debate about the nature of creativity and whether it is domain specific. If one is considered a ‘creative person’ as we like to say in informal conversations, then shouldn’t they prove to be creative in a range of circumstances and subject areas? Of course, you do get the occasional ‘renaissance man’ (person) that genuinely seems creative across the board, but it is hard to know if they have just had the circumstances to become well versed in more than one domain. Are creative behaviours, then, domain specific. Consider asking a high jumper to run the hurdles. They are skilled at running and jumping and still have extremely high levels of fitness, surely they are at top of their game in the high jump, they would simply be a champion hurdler on their first try too?!

This is also demonstrated in The Queen’s Gambit, where the American chess champion, Benny Watts (who she beats in the tournament final the next day), challenges her to speed chess. Surely, Beth will be just as masterful at this? It’s the same rules, same plays, its just a change in style of play. And yet, Benny trounced her. Repeatedly. In fact, it took her a significant amount of repetitive practice, in simultaneous games with other experts to build that new muscle. There is research supporting this case too. Baer (1994a) demonstrated that creativity training targeted at divergent thinking in a particular domain led to an increase of creativity in that area alone. Creativity ratings on tasks in other domains were not affected.

That being said, can you imagine that if Beth hadn’t walked in on Mr Shaibel playing chess by himself that she wouldn’t have found something else to be transfixed and thus a creative genius in? Perhaps that’s just her personality? (I’m not touching the complex concept of personality here, another time!).

References:

Amabile, T.M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43, 997-1013.References:

Baer, J. (1994a). Divergent thinking and creativity: A task-specific approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999), ‘Implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity’, in R. Stenberg (ed.), Handbook of Creativity, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 313–35.

Kaufman, J.C., Plucker, J.A. & Baer, J. (2008). Essentials of creativity assessment. New York; Wiley.